Clifford Donald Simak was born on August 3, 1904, in Wisconsin. He died in Minnesota on April 25, 1988. That’s thirty-three years ago as of this Sunday.

While the passage of a third of a century has dimmed his star somewhat, in his time he was well known. My local paper noted Simak’s passing, even though the Waterloo Region Record was not notably interested in matters science fictional nor in events Minnesotan. Among his notable characteristics: a humanism unusual for the science fiction of the time. Others might set human and alien against each other in total war. Simak was just as likely to have them share a porch as they watched a particularly beautiful sunset.

Unfamiliar with Simak? Here are five of his works you could sample.

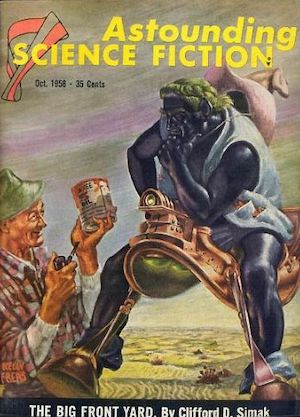

“The Big Front Yard” (1958)

In this quintessential Simak tale, rustic handy man/antique salesman Hiram Taine is startled to learn that his store basement has a new ceiling. It’s a fine ceiling, made from some indestructible material, but Taine didn’t install it. The mysteries don’t stop with the ceiling. A formerly black-and-white television has somehow become colour. Hiram’s front yard somehow opens on a completely unfamiliar vista.

The explanation is straightforward but unexpected: aliens have opened a dimensional gate in front of Hiram’s home. The renovation and the repairs were their initial, inarticulate attempts at first contact. Other men might be horrified by this intrusion of the Other into their lives. Hiram sees people who could be customers and even friends.

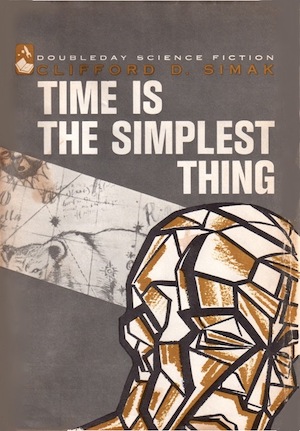

Time Is the Simplest Thing (1961)

Having learned the hard way that frail human bodies cannot withstand the rigors of interstellar travel, humanity turned to psychic exploration. Where physical exploration fails, psychic exploration succeeds. Casting astral projections to the stars, paranormals—“parries” in the vernacular—like Shepherd Blaine bring home the Milky Way’s wealth…at least, the riches that can be conveyed by a human mind. A bitterly disappointing result for most humans, but a source of great wealth for the Fishhook Corporation, which controls astral exploration.

Shepherd is too successful. After an encounter with a pink blob (who greets him telepathically with the words “Hi pal, I trade with you my mind…”), Shepherd returns home with an uninvited hitchhiker sharing his brain. Now, explorers who bring home guests vanish into Fishhook’s hospitality, never to be seen again. What happens after that is unclear. Certain that he does not want to find out what Fishhook does with (or to) the explorers, Shepherd goes on the run. He discovers that not only did he acquire a passenger out there in the stars, Shepherd himself has been transformed in…interesting…ways.

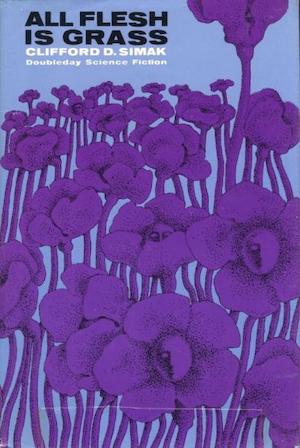

All Flesh Is Grass (1965)

Millville is an unremarkable small American town, save for the impenetrable, invisible barrier that silently manifests one day. Bradshaw Carter encounters the barrier while driving out of town; he survives the aftermath but his car does not. Carter is left to ask the same questions the other rustics of Millville will ask: Who built the barrier and why?”

The answer is—of course!—aliens. Specifically, purple flowers not of this Earth. The aliens seek harmony and fellowship. Xenophobic, insular humans, not so much. It falls to Bradshaw to search for a bridge between hopeful galactics and suspicious, violent humans. If he fails, he could be crushed in the conflict.

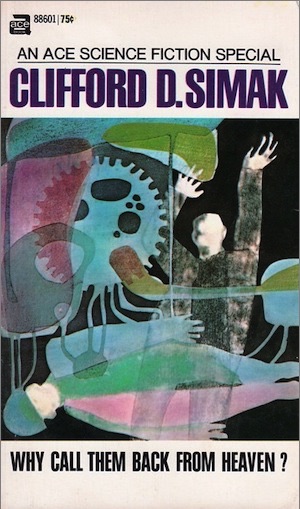

Why Call Them Back From Heaven? (1967)

Why waste your life chasing supernatural rebirth in a heavenly paradise (whose existence is a matter of mere faith) when the dead can be frozen and stored in the Forever Center until such time as they can be thawed out and revived to enjoy a very Earthly paradise?

Freezing may cost you everything you own, but surely the reward will be worth it.

By the 22nd century, there are hundred billion corpsicles on ice. Half that number of yet unfrozen humans are slogging away at miserable jobs to pay for their great tomorrow. Who is benefiting now? The Forever Center. This vast, lucrative enterprise will not tolerate even the slightest potential threat. PR man Daniel Frost stumbles across Forever Center secrets and is framed, convicted, and branded as a pariah. Daniel sets out to clear his name, but it would seem that he has little hope of challenging the establishment.

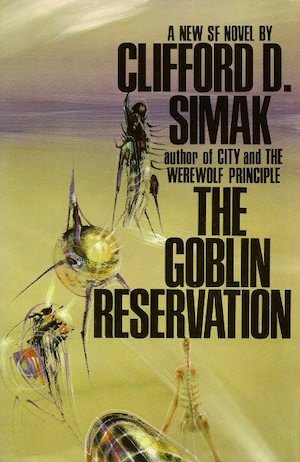

The Goblin Reservation (1968)

Professor Peter Maxwell returns to Earth from the stars to discover that he is the second Peter Maxwell to return from the stars. His first guess is that he had been intercepted by ghostly aliens in mid-matter transmission; later it becomes clear that the aliens simply duplicated Peter on their crystal planet. Two Professors Maxwell could be very awkward—who gets the faculty parking spot?—so perhaps it is for the best that the original Peter Maxwell died in an apparent accident soon after returning from the alien planet.

The world of tomorrow is an odd one, filled with aliens like the Wheelers, mythical creatures like goblins, trolls, and faeries, and even Neanderthals and English playwrights snagged from the past. Mysteriously duplicated professors seem a picayune strangeness by comparison. In this case, however, Peter was created to deliver an offer from the crystal-world aliens to sell the contents of their vast library. It is an unparalleled opportunity for Earth, a treasure which malevolent entities are determined to have for their own. Unfortunately Peter’s second, final death may follow rather quickly on the heels of the death of the original Prof. Maxwell.

***

What about City and Way Station, you ask? Other Tordotcom reviewers beat me to both.

Perhaps you are new to Simak, in which case I hope you enjoy these. If you are familiar with his fiction, please mention whichever works you feel bear mentioning next to City, Way Station, The Big Front Yard, Time Is the Simplest Thing, All Flesh Is Grass, Why Call Them Back From Heaven?, and The Goblin Reservation. The comments are below.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF(where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award and is surprisingly flammable.